I wrote an earlier post called “In a world without cookies” which was my early response to the default setting in Apple’s Safari browser. This issue has expanded such that we’ll see even fewer cookies out there, so I’m going to bring a little more light to the issue of privacy and privacy compliance in mobile, tablet and the desktop.

For the purposes of addressing privacy, the physicality of the device, whether it is a tablet, phone, or a desktop computer, can be mostly ignored. The real technical distinctions with regard to privacy are between browsers and apps. It’s also important to understand the need for advertising companies to maintain compliance with organizations like the NAI and initiatives like the OAB. Together, the OAB and NAI dictate opt-out rules that online advertising companies must adhere to.

3rd Party Cookie Blocking

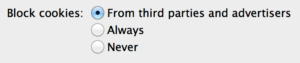

Apple’s Safari browser has a default set to block third party cookies. Firefox will soon have a similar default setting.

The most prolific obstacle in privacy and compliance is probably a result of Apple’s move to disable 3rd party cookies by default in their Safari browser. This is not just the Safari that ships on your iPad or iPhone, but all Safari browser installs, including that one on everyone’s beloved Windows machine. Now, the team behind Mozilla’s Firefox browser has pledged to do the same. Blocking by default causes two problems: advertising companies can’t do simple things like frequency cap using a cookie, and there’s no way to determine the user’s actual intent. If the default setting was to allow 3rd party cookies, a user’s intent would be crystal clear if it was set to block.

The behavior of the 3rd party cookie blocking creates even more chaos. If the setting is flipped to allow cookies, and an advertising company’s cookie is set during that time, even when 3rd party cookie blocking is turned back on the company’s cookie remains in the browser and remains totally functional. A user would have to turn blocking on and then clear all their cookies to avoid this browser behavior. This muddies the user intention waters even more.

The mess gets even messier. In order to work around the 3rd party cookie setting, many mobile advertising companies are leveraging an HTML 5 technology called Local Storage. This is a browser mechanism that works a lot like a cookie, but allows for a little more flexibility than blocked 3rd party cookies. Frequency caps are, at least, being done with this mechanism in many cases. Industry bodies like the NAI have not addressed this practice with an official policy. For the time being, frequency capping has fallen into a gray area of privacy compliance which might be why this issue hasn’t been addressed yet.

Privacy Compliance

The second obstacle is a little less obvious. As advertisers and ad technologies move deeper and deeper into mobile and tablet apps, compliance and privacy has taken a back seat. Apple shocked the ad world when it disabled device ID access to app advertisers, only to subsequently replace it with the ID For Advertisers (IDFA). The only discernable difference is that the IDFA stored on a device can be reset. iOS does not put this feature in the Privacy section of the settings, it’s buried deep in the About section. That’s not even the main problem with device IDs or IDFAs.

The main problem is that advertising companies have no way to perform the compliance practices that they need to. There’s no app for opting out of advertiser tracking. Integrating an opt-out area into every ad would consume a lot of the already limited real estate on many mobile device ad sizes. Online privacy advocates and the online advertising industry have yet to vocally address compliance concerns in the app environment.

Do Not Track (DNT)

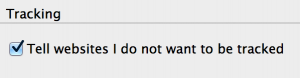

Finally, the grand daddy of noise-making problems in privacy is not isolated to mobile devices and tablets. It’s the initiative known as Do Not Track or DNT. DNT is part of a proposed set of behaviors and browser settings that aim to encourage self-policing by the advertising industry and publishers until the legislation can be worked out to enforce it. DNT starts as a setting in the web browser. The browser includes the state of this setting (DNT on or off) in requests to a publisher web site. It’s asking the publisher not to track the user when it’s turned on. That means no cookies, maybe. If you log in, it’s probably okay to get a cookie to keep you logged in. If you click on an ad, maybe it’s okay to set a cookie there so the advertiser can properly attribute the click… maybe.

Finally, the grand daddy of noise-making problems in privacy is not isolated to mobile devices and tablets. It’s the initiative known as Do Not Track or DNT. DNT is part of a proposed set of behaviors and browser settings that aim to encourage self-policing by the advertising industry and publishers until the legislation can be worked out to enforce it. DNT starts as a setting in the web browser. The browser includes the state of this setting (DNT on or off) in requests to a publisher web site. It’s asking the publisher not to track the user when it’s turned on. That means no cookies, maybe. If you log in, it’s probably okay to get a cookie to keep you logged in. If you click on an ad, maybe it’s okay to set a cookie there so the advertiser can properly attribute the click… maybe.

DNT is still just a proposal, but browsers are already showing up with the setting in their preferences. Microsoft even set the default to be “on”! Take that, Apple! By and large, however, Microsoft’s web properties, including Bing, ignore the setting completely.

The best practice a publisher or advertiser can take is to adhere to the well-established criteria for online user privacy. Consulting with levelheaded privacy experts is a good place to start. The NAI has information to help users understand online privacy and the OAB website has information for web publishers, advertisers and agencies.

Mozilla has delayed the deployment of the “default on” blocking of third party cookies. At issue are a couple of edge cases that aren’t adequately addressed by the technology.

Details can be found here: https://brendaneich.com/2013/05/c-is-for-cookie/